Losing a loved one is difficult enough without the added stress of managing their financial affairs. For many families, one of the most pressing questions is, "What happens to their debt?" It's a common source of anxiety, but with the right legal guidance, you can navigate this process with confidence.

Let's address the most important point right away: In Texas, debt does not simply disappear when someone passes away. However, it also does not automatically transfer to family members. Instead, any outstanding debt becomes the responsibility of the deceased person's estate, which must be handled according to specific rules outlined in the Texas Estates Code.

The Estate's Responsibility for Debt

When a person dies in Texas, everything they owned—their home, bank accounts, investments, and personal belongings—is gathered into what is legally known as their estate. This estate is a legal entity that steps into the deceased's shoes to pay off legitimate debts before any assets can be passed on to heirs.

Think of the estate as a temporary holding company created to finalize the person's financial life. Its primary duty, according to the Texas Estates Code, is to pay creditors based on a strict legal priority system. This process is designed to be orderly and, most importantly, to shield family members from being held personally liable for debts they did not co-sign.

Key Principles of Estate Debt Under Texas Law

To understand what happens to debt, it's essential to know a few ground rules. The executor named in the will (or an administrator appointed by the court) is in charge of this process. This is a serious fiduciary role with strict duties to manage the estate’s finances responsibly.

Here’s a step-by-step overview of how it works:

- The Estate Pays First: Before any beneficiaries receive their inheritance, all of the estate's valid debts and administration costs must be settled using the estate's assets.

- Family Is Generally Not Liable: Your family relationship alone does not make you responsible for a relative’s debt. The main exceptions are if you co-signed a loan, were a joint account holder, or in specific community property situations in Texas.

- Not All Assets Are Available to Creditors: Certain assets, known as probate and non-probate assets, are designed to bypass the estate and go directly to beneficiaries, which often protects them from creditors.

This guide will walk you through the structured process laid out by Texas law. We aim to clarify who is—and who isn't—responsible for a loved one’s debts, empowering you with the knowledge to handle this challenging time.

Understanding the Estate's Role in Settling Debts

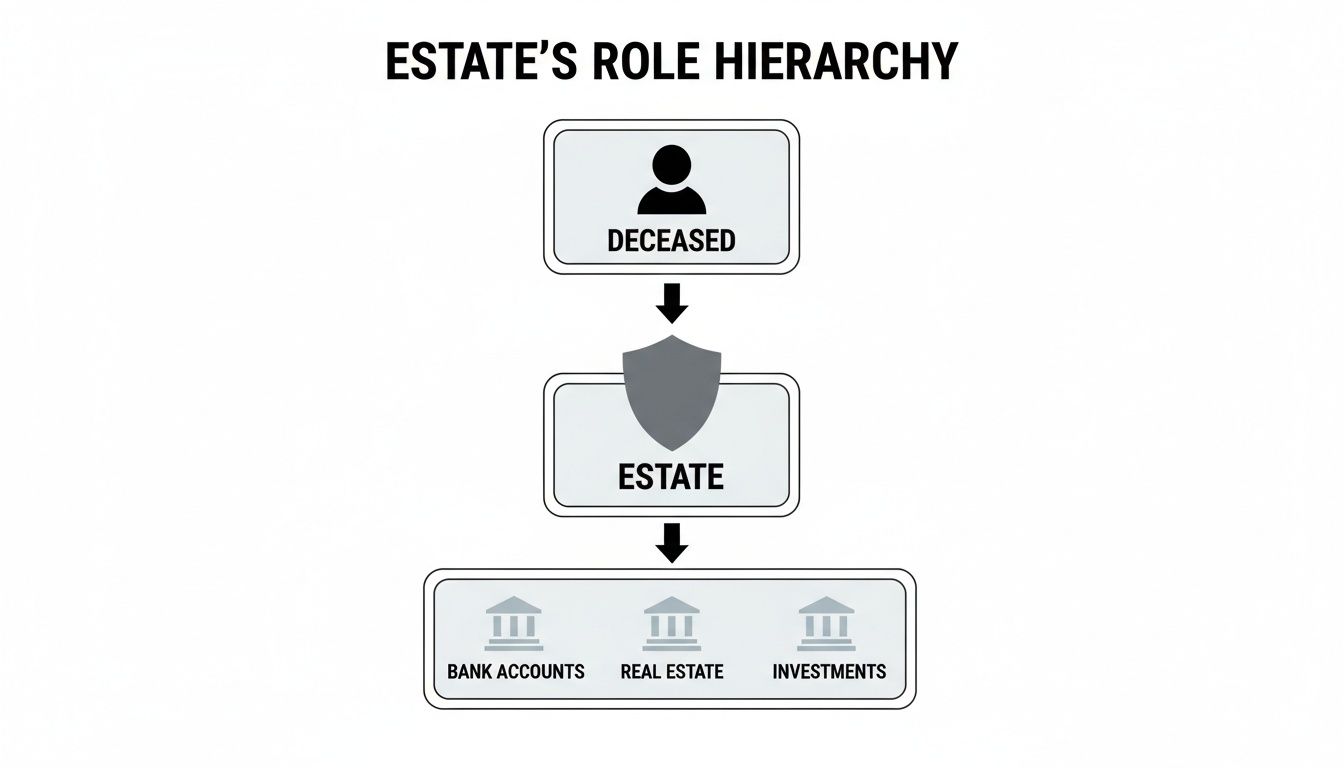

When a person passes away in Texas, their estate acts as a temporary legal container holding everything they owned. Its primary job, before any inheritance is distributed, is to settle all legitimate debts using the assets inside that container—things like cash, real estate, vehicles, and investments.

The estate provides a crucial buffer, generally preventing creditors from pursuing the personal assets of family members to pay for the deceased's debts. This process is overseen by an executor (if named in a will) or an administrator (appointed by a court), who has a fiduciary duty to manage the estate's finances in accordance with Texas law.

Probate Assets vs. Non-Probate Assets

A critical first step is understanding that not all assets are treated equally when paying debts. They fall into two distinct categories, which determines what creditors can legally access.

-

Probate Assets: These are assets owned solely by the deceased with no beneficiary designated to receive them automatically. Examples include a personal checking account, a car titled only in their name, or their share of a property owned as "tenants in common." These assets form the probate estate, which is the fund used to pay creditors.

-

Non-Probate Assets: These assets have a built-in transfer mechanism, passing directly to a named beneficiary outside the court-supervised probate process. Because of this, they are typically shielded from the estate's creditors. Common examples include life insurance policies, retirement accounts like 401(k)s and IRAs, and assets held in a living trust.

This distinction is why a child can receive a life insurance payout directly, even if their parent left behind significant credit card debt. The policy was a non-probate asset, so it never became part of the estate available to creditors.

The Executor's Critical Responsibilities

The executor serves as the fiduciary managing the entire process. Their job isn't just to distribute assets to heirs; it involves the meticulous administration of the estate's financial affairs. This includes inventorying all assets, formally notifying creditors, and paying valid claims in the strict order required by the Texas Estates Code.

Failing to follow these rules can lead to serious legal consequences, including personal liability. An executor has a significant responsibility, and you can learn more about the primary duties of an executor of an estate in Texas.

Sometimes, an estate must sell property to generate cash to cover debts. For practical advice on maximizing value in these situations, this guide on optimizing an estate sale can be very helpful.

The Reality of Debt at Death

Most people do not leave this world with a zero balance. A comprehensive study revealed that 73% of Americans died with outstanding debt, with an average balance of $61,554 (including mortgages).

The types of debt are also revealing:

According to the study, 68% of these individuals had credit card debt, 25% had auto loans, and 6% were still paying student loans. These debt findings on ABC News show how common it is for families to face a loved one's financial obligations.

These figures underscore the importance of the executor's role. They must carefully navigate a complex web of financial obligations to protect the estate and ensure that any remaining assets are distributed correctly to beneficiaries.

How Texas Law Prioritizes Creditor Claims

When an estate owes money, not all debts are treated equally. The Texas Estates Code establishes a clear “pecking order” for who gets paid first. Think of it as a priority line—some creditors are legally entitled to go to the front.

This legal hierarchy is a strict rule, not a suggestion. An executor who pays a lower-priority claim, like a credit card bill, before a higher-priority one, like funeral expenses, could be held personally liable for the mismanaged funds. Adhering to this priority is essential for any executor to fulfill their fiduciary duties and avoid financial risk.

This diagram illustrates how the estate serves as the central point for managing assets and settling claims.

As shown, the estate acts as a protective shield. It gathers the deceased's assets to systematically pay off obligations before any inheritance is distributed to the heirs.

The Classification of Claims in Texas

The Texas Estates Code categorizes claims against an estate into different classes, ranking them by priority. This system provides the executor with a clear roadmap, specifying the exact order for paying bills.

When an estate has insufficient funds to cover all debts (an "insolvent estate"), this order becomes even more critical. The executor must pay each class in full before moving to the next.

Here’s a practical breakdown of how an executor must pay claims from an estate's assets, as mandated by Texas law.

Texas Estate Claim Priority: An Executor's Guide

This table outlines the legal order in which debts and expenses must be paid from an estate under the Texas Estates Code.

| Priority Class | Type of Claim or Expense | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | Funeral & last illness expenses (up to $15,000 total) | Hospital bills from the final days, cost of the burial service |

| Class 2 | Estate administration expenses | Court filing fees, executor's commission, attorney fees |

| Class 3 | Secured debts (from the sale of the collateral) | Mortgage paid from the proceeds of the home sale |

| Class 4 | Unpaid child support | Arrears owed from a court-ordered support obligation |

| Class 5 | State taxes | Unpaid property taxes on the deceased's home |

| Class 6 | Cost of confinement | Expenses owed if the deceased was incarcerated |

| Class 7 | State medical assistance reimbursement | Money owed to the state for Medicaid benefits received |

| Class 8 | All other claims (unsecured debts) | Credit card balances, personal loans, utility bills |

This structured system ensures an orderly process for winding down a person's financial affairs, preventing a chaotic free-for-all among creditors.

Secured vs. Unsecured Debts

A key distinction in this hierarchy is between secured and unsecured debts. A secured debt is tied to a specific piece of collateral. The most common examples are a mortgage (secured by the house) and a car loan (secured by the vehicle). Secured creditors have a significant advantage because they can repossess the property if the loan is not paid.

An unsecured debt, on the other hand, has no collateral. This category includes credit card balances, medical bills, and personal loans. As shown in the table, these creditors are in Class 8—the lowest priority.

Real-World Scenario: An estate has $30,000 in assets. It owes $5,000 for funeral expenses, $5,000 in administrative costs, and $50,000 in credit card debt. The executor must first pay the Class 1 funeral bill and Class 2 administrative costs in full ($10,000 total). The remaining $20,000 goes to the credit card company. Because the estate's funds are now depleted, the creditor must legally write off the remaining $30,000 balance. The executor has fulfilled their duty, and the family is not liable for the shortfall.

Properly classifying and paying claims is a cornerstone of successful estate administration. A knowledgeable Texas estate planning attorney can provide invaluable guidance, ensuring the executor navigates this process correctly and protects both the estate and themselves.

How Common Types of Debt Are Handled

While legal principles provide a framework, families often want to know what happens to specific debts like the mortgage or medical bills. Let's break down how common debts are managed in Texas after someone passes away.

Understanding the practical steps for each type of debt can provide significant peace of mind. The outcome typically depends on two key factors: whether the debt is secured or unsecured, and whether someone else co-signed the loan.

Mortgage and Home Loans

A mortgage is a classic secured debt. The loan is tied directly to the house, which gives the lender the right to foreclose if payments stop. When a homeowner dies, the mortgage debt does not disappear.

The executor and the family generally have a few options:

- Continue Payments and Keep the Home: If an heir wishes to live in the home, they can often assume the mortgage or refinance it in their own name. Federal law provides protections to make it easier for relatives to take over the loan.

- Sell the House: The home can be sold during the estate administration process. The proceeds are used first to pay off the mortgage, with any remaining funds going back into the estate to cover other debts or be distributed to beneficiaries.

- Surrender the Property: If the home is "underwater"—worth less than the mortgage balance—or if no one wants the property, the executor can surrender it to the lender, who will then likely foreclose.

A critical duty for the executor is to continue making mortgage payments during probate, provided the estate has sufficient cash, to prevent foreclosure while affairs are being settled.

Credit Card Balances

Credit card debt is the most common type of unsecured debt. With no collateral backing it, credit card companies are low on the payment priority list—a Class 8 claim in Texas.

This means they get paid last. All higher-priority claims, such as funeral expenses, legal fees, and secured debts, must be settled first.

If the estate is insolvent (lacks enough money to cover all its debts), credit card companies often receive a fraction of what they are owed, or nothing at all. The remaining balance is legally written off. Family members, including spouses who were merely authorized users on an account, are not responsible for this debt.

The major exception is if a spouse or another individual was a joint account holder. If your name is on the account as a co-owner, you are fully responsible for the entire balance. This detail often catches families by surprise.

Medical Bills and Healthcare Costs

Like credit card debt, medical debt is unsecured and falls into the Class 8 claim category. It is only paid after all higher-priority debts are settled. Hospitals and doctors cannot legally pursue children for their parents' medical expenses.

One important exception is Medicaid. If the deceased received long-term care benefits, the state may seek reimbursement from the estate through the Medicaid Estate Recovery Program (MERP). This is a complex area, and it is crucial to understand how to avoid Medicaid estate recovery through proactive estate planning.

Auto Loans

A car loan functions like a mortgage on a smaller scale. It is a secured debt with the vehicle as collateral. If payments cease, the lender has the right to repossess the car.

The estate's options are straightforward:

- Keep the Car: An heir can take over the vehicle by refinancing the loan or paying it off.

- Sell the Car: The executor can sell the vehicle, use the proceeds to pay off the loan, and add any surplus to the estate's general funds.

- Return the Car: If no one wants the vehicle, it can be voluntarily surrendered to the lender. The lender will sell it and may file a claim against the estate if the sale does not cover the full loan balance.

When a Family Member May Be Responsible for a Debt

One of the first questions families ask is, "Am I responsible for their debts?" It's a valid concern, but the general rule in Texas is no. You are not automatically liable for a relative's debts simply because of your relationship. The debt belongs to the estate, and the estate is responsible for settling it.

However, there are a few specific situations where you could be held personally liable. Understanding these exceptions is key to protecting yourself from creditors.

You Co-Signed a Loan

This is the most direct way to become responsible for another person's debt. When you co-sign a loan—whether for a car, a home, or a personal loan—you make a legally binding promise to the lender. You are telling them, "If the primary borrower cannot pay for any reason, including death, I will pay the entire balance."

This is a personal contractual obligation, not an estate issue. The lender does not have to wait for the probate process; they can come directly to you for payment as soon as the loan defaults.

You Are a Joint Account Holder

Sharing a joint credit card or bank account also creates personal liability. As a joint account holder, you are a co-owner of the account and all the debt associated with it.

For example, if you and your spouse shared a joint credit card, you are both considered 100% responsible for the entire balance. After your spouse passes, the credit card company has the legal right to demand that you pay the full amount. This is a critical distinction from being an "authorized user," which generally does not create the same legal obligation.

While credit card debt is paid by the estate first, family members can become liable if they co-signed or shared the account. In community property states like Texas, a surviving spouse may also be responsible for certain debts. Learn more about how credit card debt is handled after death on Experian.com.

Community Property Rules in Texas

As a community property state, Texas laws can significantly impact surviving spouses. As a general rule, most debt incurred by either spouse during the marriage is considered community debt. This means both spouses may be responsible for it, regardless of whose name is on the account.

For example, if your spouse opened a credit card solely in their name but used it for shared household expenses, that debt could be classified as community debt. This makes the estate—and potentially the surviving spouse's share of community property—liable for repayment. Navigating these rules requires a clear understanding of understanding marital debt liability. Consulting a Texas estate planning attorney is the best way to protect your assets in these situations.

A Practical Checklist for Managing Estate Debts

Serving as an executor can feel overwhelming, but a step-by-step plan can make all the difference. This checklist provides a roadmap for managing an estate’s debts confidently and in compliance with Texas law.

A common mistake is rushing to pay bills. While it may seem responsible, paying claims out of order can create personal liability for the executor. The first step is always to pause, get organized, and follow the correct legal sequence.

Initial Steps for the Estate Administrator

Before paying creditors, you must get a complete financial picture. This is the information-gathering phase.

- Locate All Key Documents: Gather the will, any trust agreements, bank and investment statements, property deeds, vehicle titles, and recent tax returns. These documents form the basis of the estate's inventory.

- Secure the Assets: Protect the estate's property by changing locks on the home, securing valuable items, and notifying financial institutions to prevent unauthorized access.

- Obtain Multiple Death Certificates: You will need several official copies for banks, government agencies, and other institutions.

Notifying and Managing Creditors

Once assets are identified and secured, you can address the debts. This part of the process is strictly governed by the Texas Estates Code.

Following the correct procedure for notifying and paying creditors is a legal requirement. Proper management protects both the estate and the executor from future disputes and personal liability.

A formal notice to creditors is a key part of the probate process. This involves publishing a notice in a local newspaper and sending a direct, certified notice to any known creditors. This action starts a legal deadline for them to file a formal claim against the estate.

Once claims are submitted, your duties include:

- Verify Each Claim: Review each bill to ensure the debt is legitimate and the amount is accurate.

- Accept or Reject Claims: Formally accept valid claims and reject any that are questionable or invalid.

- Pay Claims in Order: Pay all accepted claims strictly according to the priority list established by Texas law. Remember that unsecured debts like credit cards are paid last.

When debt collectors contact you, be firm and professional. Inform them that you are the estate administrator and provide your contact information. Never promise to pay a debt from your personal funds. Your duty is to pay valid estate debts from estate assets, and only when the law permits.

Common Questions About Debt After Death in Texas

When you're grieving, legal questions are the last thing you want to worry about. Here are straightforward answers to some of the most common concerns we hear from Texas families.

Can a Creditor Take My Inheritance to Pay for My Parent’s Debt?

The short answer is no. Your inheritance is protected from your parent's creditors. Texas law is clear: the estate must settle all valid creditor claims before any assets are distributed to beneficiaries.

Think of the estate as a business closing down. It must pay its debts before distributing profits to its owners—the heirs. Once all debts are paid and you receive your inheritance, it is yours, free and clear. Creditors cannot pursue you for it.

What Happens If the Estate Has No Money to Pay Debts?

Sometimes, an estate's debts exceed its assets, making it "insolvent." In this situation, the executor must follow the legal priority list, paying creditors in order until the money runs out.

Once the estate’s funds are depleted, any remaining unsecured debts—such as credit card bills or medical expenses—are typically written off. Family members are not required to pay the shortfall from their own pockets.

Do I Have to Speak with Debt Collectors After a Loved One Dies?

Unless you are the court-appointed executor or administrator, you are not legally obligated to speak with them. If a debt collector contacts you and you are not managing the estate, you should direct them to the executor.

The most important rule is to never promise to pay the debt personally. Simply provide the contact information for the executor or the estate’s attorney. The executor is the only person with the legal authority to manage these communications and handle creditor claims correctly.

If you’re managing an estate or planning your own, contact The Law Office of Bryan Fagan, PLLC for a free consultation. Our attorneys provide trusted, Texas-based guidance for every step of the process.